You move to a new city to start an exciting new job — Congratulations! — and you find a place to stay that the map suggests is about a 20 minute walk to work. Now that you’re in your new place, you check if there’s a quicker way to get in, and find a bus that takes 10 minutes plus a minute of walking on both ends. So the bus should be quicker, but you know there’s things that can affect how long it takes, including delays and traffic. And getting to the stop early enough so you don’t miss the bus! You decide you’ll do an experiment and try both ways for a few weeks to see which one is quicker on average.

Each morning, you choose whether to walk or go by bus, and carefully measure the time it takes using your watch. After a few weeks, you work out it takes a disappointing 22 minutes to go by bus on average (from ready-to-leave to arrival), while the average time for walking is 18 minutes. You decide that walking is quicker, and that’s how you’ll get into work from now on.

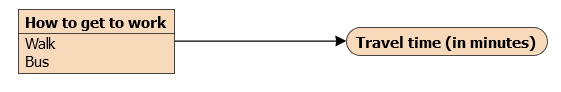

Here’s a little causal BN for how you think your experiment looks:

But there might be a problem with this simple picture. On the cold and rainy days, you decided to go by bus, and on the nice sunny days, you decided to walk. That means the weather affected your choice. Other things affected your choice, too, like your mood, how energetic you felt, what time you got up, how crowded you thought the bus would be. Many of these things don’t just affect your choice, they also affect how long it takes to get in. Statisticians and causal researchers call these common causes confounders.

So here’s another causal BN for your experiment, this time with all the things we mentioned that might have affected both your choice and how long it takes (i.e., with all the confounders):

Why is this a problem? Because any of these other things might be the main factor that influences how how you get to work is related to travel time. Suppose on sunny days, the bus is on time, but on rainy days, it’s heavily delayed. In that case, it would be a good deal quicker for you to catch the bus on sunny days than walk. So if you’re just trying to find the fastest way in on average, your best bet might be to always catch the bus.

There’s a few ways to solve this. For example, if, in your experiment, you chose at random, you wouldn’t have had this problem. Why? And given all the things that can affect your choice, where do you think the idea of free will fits into this picture? Randomness and free will are things we’ll look at in future posts.

Pingback: Choosing at random – Causal Bayes